I was talking to some friends last weekend about how much pain reviews can cause. Even the good ones can hurt because writers are mostly neurotic and we will find the phrase or the one word that is less than complimentary and then we obsess about that word until we’ve driven ourselves into a right, old funk.

And then I received word about my latest review from England.

I will never whine about a review again. Ever. Because after this one? I’m never going to read another review. I’m just going to reread these incredible words that Melvin Burgess, one the most significant YA authors in UK, wrote about my book. I might set them to music. Or turn them into an epic saga-length, ego-soothing poem.

It does not get any better than this. (Review originally published in the The Observer, Sunday 30 January 2011. )

“There is a great deal of dross written in teenage fiction, nearly all of which seems to end up on my desk. But from time to time, you come across a book that reminds you just why this is such an exciting – and exacting – field.

Wintergirls has many of the obsessions of current teen fiction, including the use of repetition and formatting to convey the state of mind of Lia, the protagonist, and the incredibly intense interior dialogue – so private, so shut off from the outside world, and which makes this particular novel so startling and memorable.

The plot is familiar enough. Our heroine, Lia, already ill, is sent on a vicious downward spiral into anorexia and self-harm by the news that her ex-best friend, Cassie, has died alone in a motel room. The desperation and self-hatred this triggers are set against Lia’s cleverness at hiding it from her separated parents, busy mum (Dr Marrigan), selfish father (Professor Overbrook) and well-meaning but unimaginative stepmother, Jennifer.

Meanwhile, the vengeful ghost of Cassie comes to haunt Lia and does her utmost to convince Lia to follow her all the way to self-destruction.

Lia’s fragile efforts to find a way out of her nightmare seem doomed to failure, but there is hope. There is love – complicated, but genuine, from both parents and stepmother, while her relationship with her little stepsister, Emma, is simple and guileless.

The novel sets a terrific dramatic pace. As soon as we realise that Cassie phoned Lia 33 times the night she died, and that Lia failed to pick up, the danger Lia faces is plain. But it is the raw stylistic power that makes this so memorable. Those clever word games are used to powerful effect, from the endless repetitions of Lia’s self-hating mantras to the crossed-out words that give the lie to her own thoughts.

The true nature of anorexia is made painfully clear. Lia starves herself because it is the only control she has over her disintegrating personality; anyway, why feed something so hateful? She cuts herself not to cause pain, but to let the pain – and the dirt – out. The dirt in this case is, of course, herself. As with the plotting, this fractured and utterly convincing interior monologue is intercut with the rather bored face she presents to the world around her.

And yet, throughout, there is the feeling that if somehow you could only reach in and talk to this girl, you could save her life. It’s an exhausting novel to read: brilliant, intoxicating, full of drama, love and, like all the best books of this kind, hope. It would be rare to find a novel in mainstream adult fiction prepared to pull out the dramatic stops this far, and difficult to imagine one in recent years that was prepared to be so bold stylistically. It’s a book that will be around for many years. It may not be an original piece, as these tricks have been pulled before in teen fiction. Yet it pulls them off with more skill and effect than anything I have ever read.”

Thank you, Mr. Burgess. Thank you very much indeed.

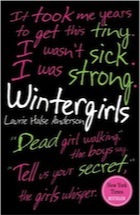

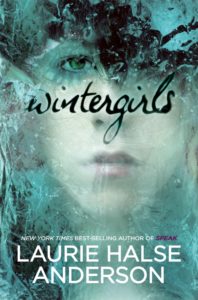

UK cover US cover