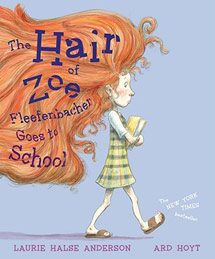

Zoe’s Secrets

How the Book Began:

Where did the idea for Zoe come from?

My family room.

I have one daughter, Stephanie, who was born with lovely red hair. I have another daughter, Meredith, who has a rather energetic personality.

Out of a strange melding of these two girls came the idea for ZOE: a child born with a quarter acre of crazy red hair that had a personality of its own.

In the early drafts, the story wasn’t quite a story. It turned out that just having cool hair was not enough. This explained the rejections I received for the book in the mid 1990’s. (The story was VERY DIFFERENT from its current form!) When a rejection would come in, I’d pout, and keep tinkering with it.

Both of my girls went off to kindergarten and then first grade. Meredith’s exuberant personality was not appreciated by all of her teachers. When Meredith was identified as ADHD, we were confused. It didn’t feel right to force our child into something she was not made to be. But clearly she had to learn to adapt to a classroom setting. What to do?

With this personal drama unfolding in the background, I continued to edit and rewrite Zoe’s story. I added the somewhat intimidating character of Ms. Trisk and clarified the conflict: Zoe has to learn to follow the rules of first grade. But that makes her sad.

My daughter Meredith, meanwhile, was growing up. She was blessed with a couple OF teachers who really valued her qualities and personality. Meredith learned how to adapt to a school setting. The school learned to adapt to her. And I finally figured out how to write Zoe.

An editor I sent it to loved it, but said that too many “hair books” had just come out, and he wanted to hold on to it for a bit. About five years later, he called me up and said the time had come. The world was waiting for Zoe.

And my daughter?

She was so inspired by the teachers who respected who she was and helped her figure out her own leaning style, that she became an education major in college. She graduated in May and is now an 8th grade science teacher working near the Pennsylvania/Maryland border.

THE HAIR OF ZOE FLEEFENBACHER GOES TO SCHOOL is dedicated to my daughter Meredith.

What Happened to Pluto?

Yesterday’s post covered the background and writing process of THE HAIR OF ZOE FLEEFENBACHER GOES TO SCHOOL. It took, um…. years to write the book and have it published. (I point this out to anyone who is just joining the field of children’s literature and thinks they have a great picture book idea that will make them eight million dollars in time for Christmas.)

In the critical scene of ZOE, the teacher is trying to demonstrate how the planets in our solar system revolve around the sun. In the early drafts of the book, there were nine planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto.

Then—while Ard Hoyt was working on his preliminary sketches—Pluto was demoted.

Time for another revision!

I thought about making a scientific political statement, like asking Ard to draw in a poster in Ms. Trisk’s classroom that said something like “Bring back Pluto!”, but wiser heads prevailed.

Picture Book Basics:

So…. picture book writing!!!

What follows is my approach to writing picture books. (Yep, it’s all my copyright, but may be reproduced for classroom use.) There are many different variations on this, of course, but I thought guidelines might be useful for some of you.

When I am thinking of a picture book idea, I am always aware of the structural limitations the form imposes:

1. A picture book has 32 pages.

2. This means a picture book has (usually) 16 2-page spreads.

3. Good picture books usually have fewer than 750 words. Fewer than 500 is better.

4. A picture book needs a beginning, a middle, and an end.

5. A picture book has character, conflict, and character growth that is a result of the conflict (Usually! “Quiet” picture books, sometimes called “mood pieces” (think GOOD-NIGHT MOON) are noticeably short on conflict and character growth. They are also wicked hard to get published.)

6. Picture book writing tends to be short on narrative description. Descriptive details are taken care of in the art.

7. (Warning — biased statement ahead) Picture book stories build the stage upon which great art can be committed. The illustrator is more important than the author.

8. The unfolding of the story must provide the artist with varied settings and perspectives for illustration purposes. No talking heads.

9. Authors have no control over the illustrations of picture books, unless they choose to illustrate them on their own. Don’t waste any energy fussing abut this. Focus on your story.

10. Picture book writing is the essence of story structure boiled down to the barest of bones. It’s way harder than it looks, and incredibly satisfying.

I was just asked on Twitter if I prefer the novel form or the picture book form. The answer is “Yes.” I really like having different forms to work on. I can take as many years tinkering with a picture book as a novel. It may only have a couple hundred words, but they have to be the exact right words in the exact right order! But the subject matter of my picture books tends to be a whole lot lighter than my novels and that is a nice break for my soul.

Do you get to know your picture book characters as well as those in your novels?

I know them on a completely different level, like the way you knew your best friend in second grade.

I would love to know more about how long it takes, from idea to published!

ZOE is my seventh picture book. So far the average time from initial idea to book-on-the-shelf has been four years. ZOE took longer because the story was “resting” in my drawer for several years.

[Today] you said that the illustrator is more important than the author but that the author has no control over the illustrator. That seems stressful. Does that just apply to the beginning of the process? Is there a point at which the author does have some control over the illustrator? How does the illustration process work?

The fact that authors have basically no control over their illustrations freaked me all the way out at first. But I got over it. The truth is that artists bring their own vision to the story and (in my case, at least) it’s a much more creative and energetic vision that the author has. In my non-fiction picture books, Thank you, Sarah and Independent Dames, I had a little input and was able to share my research with my illustrator, Matt Faulkner. With ZOE, I was sent the early sketches (this is very common) by my editor and was able to have a discussion with the editor about them. There was one tiny reality glitch, I believe, in the spread where the hair is out in the hall while the family has a meeting with the principal. I was able to point that out.